Who actually owns supermarkets in Hong Kong?

In Hong Kong, “supermarket owners” usually fall into three buckets: big chains run by large corporate groups, mid-sized specialty grocers backed by property or retail groups, and true independents (single stores or small local clusters). That ownership mix matters because it shapes everything from pricing power to store format, supplier terms, and how aggressively a brand can expand.

At the top end, the market is dominated by chain supermarkets owned by major groups. PARKnSHOP sits under AS Watson Group, which is part of CK Hutchison’s retail portfolio so it operates with the scale, logistics, and buying leverage you’d expect from a diversified conglomerate. On the other side, Wellcome is owned by DFI Retail Group, and it’s positioned as a mass network with large store coverage. For readers who aren’t in the trade, a useful way to frame this is: most “supermarket ownership” in Hong Kong is corporate ownership, where decisions are made centrally (pricing bands, promo calendars, private label strategy, distribution standards) and then rolled out across hundreds of stores.

There’s also a meaningful layer of specialty and premium operators that look like supermarkets to shoppers but are often subsidiaries or portfolio businesses of larger groups. A clear example is YATA, which is described as a principal subsidiary within Sun Hung Kai Properties’ non-property business portfolio showing how Hong Kong property groups sometimes own retail brands as part of a broader ecosystem around malls and foot traffic. These operators often compete less on lowest price and more on import strength, product curation, and “destination shopping,” and their ownership structure tends to prioritize consistency, brand feel, and mall synergy as much as grocery margin.

You have independents and small groups: neighbourhood grocers, fresh-focused mini-markets, and small chains with a handful of locations. They’re usually privately owned, and they survive by being faster than the big chains at local assortment (specific produce, cultural staples, ready-to-eat), service, and convenience. In practice, the key difference isn’t just size it’s leverage: chains with group ownership can negotiate better supplier terms and run sophisticated distribution, while independents win by tight local relevance and tighter feedback loops with customers.

What supermarket owners in Hong Kong earn money from?

For many supermarket owners in Hong Kong, groceries are only one slice of the profit picture. The real money is often in the parts of the store and the business model that scale well: higher-margin categories, paid placement from brands, and services that create repeat visits without adding much labour.

One major income stream is higher-margin non-food. Household goods, toiletries, cleaning products, baby items, basic health products, and small home essentials often carry better margins than fresh food. These items also have steadier demand and lower wastage risk. When rent is high, owners lean into product mixes that don’t spoil, don’t need skilled handling, and don’t create daily shrink.

Another driver is private label. Store-owned brands let supermarket groups control pricing, packaging, and supply terms, and they keep more margin compared with reselling national brands. Private label also gives owners a lever during cost swings: they can adjust pack sizes, reformulate, or switch suppliers without rebuilding the whole shelf strategy.

Then there is supplier-funded marketing inside the store. Brands pay for end-cap displays, gondola ends, eye-level shelf positions, checkout placement, sampling stations, in-store posters, and catalogue features. For owners, this is attractive because it brings cash support into the business without relying on a small margin per item. The bigger the chain, the more structured this becomes, with planned promotional calendars and pricing events that suppliers buy into.

Convenience services can add incremental profit too. Ready-to-eat counters, bakery items, cut fruit, meal kits, and hot snacks can produce strong margins because customers are paying for preparation and speed. Owners also make money from complementary services such as parcel pickup, bill payment counters, prepaid top-ups, and gift cards, where the store earns a fee and gains extra foot traffic that converts into baskets.

A quieter but important source is trading terms with suppliers. Beyond the wholesale price of goods, owners may negotiate rebates tied to volume, early-payment discounts, marketing support, and return arrangements for slow-moving stock. These terms can materially change profitability, especially in a market where headline retail prices are visible and price competition is constant.

Finally, digital channels create new profit pools. Online ordering, click-and-collect, and delivery can generate service fees, and they support larger baskets when shoppers build carts at home. Loyalty programs and app coupons also help owners earn more by steering customers toward higher-margin products, smoothing demand across the week, and reducing waste through targeted markdowns near expiry.

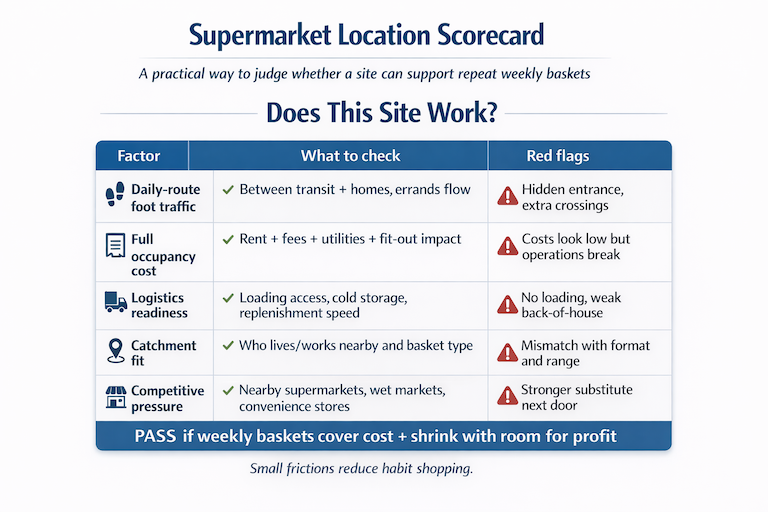

How supermarket owners choose store locations

Supermarket owners in Hong Kong pick locations by working backwards from one question: can this site generate enough weekly baskets to cover rent, staffing, and shrink while still leaving room for profit. Because rent is high and space is limited, owners care less about “nice addresses” and more about repeat buying. The best sites sit on daily routes between MTR exits and housing estates, beside bus interchanges, under residential towers, or inside malls where families already do their weekly errands. If customers must take a lift, cross a busy road, or walk past too many alternatives, foot traffic drops fast.

Rent is judged against what the store can realistically sell per square foot. Owners look at the full occupancy cost, not just headline rent: management fees, air-con charges, loading access costs, and renovation spend all change the numbers. A cheaper rent is not always better if the shop can’t take frequent deliveries or if storage is poor, because fresh and chilled lines need reliable back-of-house space. Many owners would rather pay more for a site with strong logistics (a proper loading bay, cold storage capacity, and easy replenishment) than save rent and lose sales to empty shelves, slower restocks, and higher spoilage.

Catchment area is the third leg of the decision. Owners map who lives and works within a short walk, then match that to the format. Dense family estates support larger baskets and more fresh; office-heavy zones skew toward ready-to-eat, snacks, and convenience staples; higher-income pockets can support premium imports and curated ranges. They also check what competitors already cover in that radius, including wet markets, convenience stores, and nearby supermarkets. A location can look busy but still be weak if the shoppers are already loyal to a cheaper chain next door or if the area’s buying habits favour wet-market fresh over packaged produce.

Before committing, strong operators test assumptions on the ground. They count foot traffic at different hours, watch where people come from and where they go next, and note whether the flow is “commuter rush” or “daily errands.” They also examine access points: stairways, escalators, street crossings, and visibility from main walkways. In Hong Kong, small frictions matter. A few extra minutes of walking, a poor lift lobby, or a confusing entrance can be the difference between a store that becomes a habit and one that stays “only if I’m nearby.”

How owners decide what to stock

Hong Kong supermarket owners decide what to stock by balancing three forces: what people in the neighbourhood actually buy, what the store can make money on, and what will move fast enough to avoid waste. Most owners start with a core range that never leaves the shelves rice, noodles, cooking oil, eggs, bread, milk, bottled drinks, cleaning supplies then tailor the rest to the local mix of families, commuters, students, and office workers. In an estate-heavy area, bigger pack sizes, lunchbox items, and family staples tend to perform well. Near offices and transport hubs, the winning range shifts toward ready-to-eat, snacks, coffee, chilled drinks, and grab-and-go meals that fit short shopping trips.

Margins shape the shelf just as much as demand. Fresh food can attract foot traffic, but it brings higher labour costs, spoilage risk, and daily price pressure. Packaged groceries often have tighter price competition, so owners look for categories where they can still earn a healthy return without slowing stock turnover private label, household goods, toiletries, baby products, simple health items, and chilled convenience lines are common examples. Owners also watch basket behavior: products that complete a basket (sauces, seasonings, side dishes, drinks) can be more valuable than a single high-volume item because they lift average order value without needing extra space.

Seasonal buying is where experience shows. Owners plan around local habits and calendar spikes: Lunar New Year gift packs and cooking ingredients, mid-autumn mooncakes, summer cold drinks and ice cream, back-to-school snacks, and winter hotpot items. They build these displays early, secure supply before prices rise, and reduce slow-moving lines to free space. For fresh and chilled, they tighten orders and adjust delivery frequency rather than overstocking, because the cost of throwing stock away can wipe out the margin they hoped to earn.

The best operators run this like a weekly loop. They review what sold, what sat, what had high shrink, and what triggered customer complaints. They keep a short list of “must win” items that customers expect to find every time, and they give themselves limited space for trials new flavours, new imports, or trend-driven items. If a test item doesn’t hit a clear sales target, it goes. In a market where storage is tight and rent is unforgiving, shelf space is treated like cash: it has to earn its keep.